“This is not the time for high art,” BBC presenter Hazel Irvine announced as coverage of the Olympics closing ceremony began. “It’s time for a sing-song.” After an opening ceremony marred by the weather (“wet and extraordinary,” as Irvine’s commentary partner Andrew Cotter put it) and the subject of a series of fabricated squabbles (Donald Trump called it a “disgrace,” prompting artistic director Thomas Jolly to revise his script for the ending), this Paris finale played it safe. Less high art, more pop concert.

At the opening in the Tuileries, where the Olympic flame has spent the past two weeks, French singer Zaho de Sagazan stomped around in Doc Martens while a choir warbled along to “Sous le Ciel de Paris” (“Under the Sky of Paris”). She was just the first of many artists on a night where music put sport front and center. French indie rockers Phoenix at the Stade de France were joined by artists from around the world: fellow countrymen Kaminsky and Air, as well as Cambodian rapper VannDa, Belgian singer Angèle and Ezra Koenig of Vampire Weekend.

Thomas Jolly’s direction – both the opening and closing ceremonies – at times recalled the frustrations of French Nouvelle Vague cinema. Some scenes were ponderously introspective (a shot of star swimmer Léon Marchand carrying the last flicker of the Olympic flame was pure Truffaut) and preferred to remain entirely unhurried. Perhaps this is why the BBC allowed an extra 25 minutes after the event’s scheduled end before the 10am News began (it still lasted longer). With running times of four and two and a half hours respectively, Jolly’s ceremony would make Jacques Rivette look at his watch.

But inside the Stade de France, there was relief. Successful Olympics – phew. Fueled by two weeks of – if the rumors are to be believed – chocolate muffin-fueled marathon sex sessions, the Olympians marched into the Stade de France and danced to Joe Dassin’s “Les Champs-Élysées” and Queen’s “We Are the Champions” before the live music began. That set the tone for an evening that had nothing to do with the art of Beijing or the Carnival of Rio, but plenty of danceable music.

When the artistic elements finally came into focus, Jolly took viewers on a journey into, as the BBC communications team put it, “the past, present and future”. A trippy light show served merely as a backdrop for the arrival of a dancer in a gimp suit adorned with gold feathers (perhaps symbolising the audience’s relentless desire for medals). What followed was a maximalist reinterpretation of the origins of the Olympic Games. Cotter and Irvine were on hand, as always, to live-translate the rather offbeat narrative that unfolded on stage, a sharp mix of kabuki, fetish wear and Tron.

Closing ceremonies don’t carry the same expectations as opening ceremonies. Clare Balding, speaking on BBC One during the build-up, described it as “the fun part”. Still, Jolly’s portentous invocation of the importance of Olympic brotherhood didn’t quite reach the same “fun” heights as, say, the women’s breakdancing. Given the reported tens of millions of euros it cost to stage the ceremony, couldn’t Australian viral sensation Rachel Gunn – aka Raygun – have been enticed to repeat her performance?

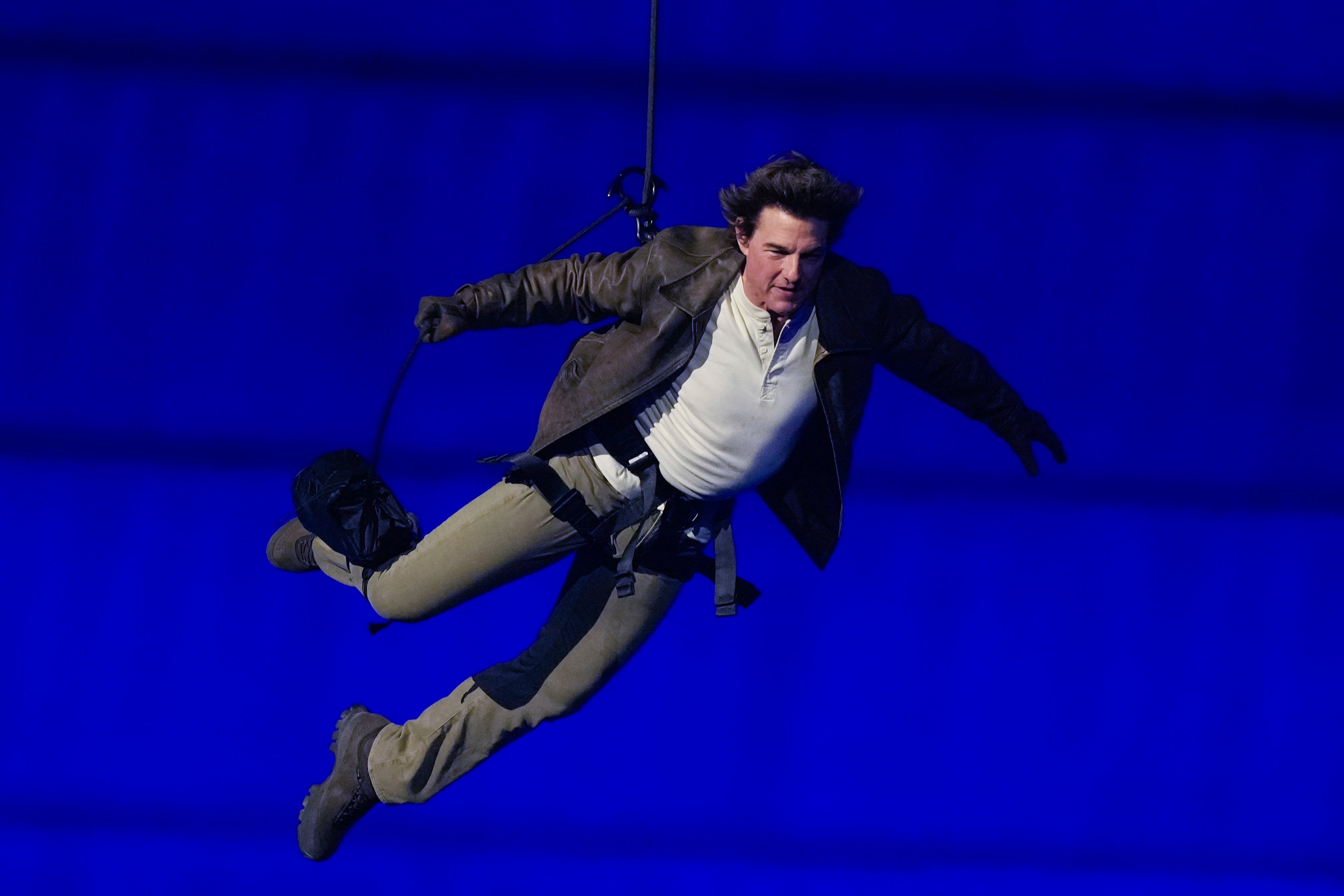

“That’s what everyone really comes for: the speeches,” quipped Cotter (who has a good quip) as the shuffling music festival atmosphere gave way to the bureaucratic part. But those who survived that boredom were rewarded with the handover to 2028 hosts, Los Angeles. LA Mayor Karen Bass took the flag and began the American invasion (LA went well over the normal 12-minute rule). A wobbly rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” was followed by the highly anticipated sight of 62-year-old Tom Cruise (looking more and more like his Madame Tussauds doppelgänger) floating down from the stadium’s rafters. LA artists Red Hot Chili Peppers, Billie Eilish and Snoop Dogg played for us live from sun-drenched Venice Beach. A stark warning, if one was needed, about what the US is willing to invest to maintain its soft power hegemony.

This closing ceremony highlighted the problems of the opening match. The Stade de France – a stadium with 80,000 seats – proved to be a large enough canvas for the theatrical elements of the proceedings. And unlike the rain-smeared camera footage from across the Seine, the joy and excitement on the faces of each athlete was clearly visible. Broadcasters around the world, meanwhile, must have been relieved. The show was rehearsed; the comments from the commentary box were obviously prepared. The dancers and cameras in the stadium moved in perfect sync.

After two weeks of seamless sporting action, the high-class pantomime of an Olympic ceremony always feels a little disappointing. But at least Jolly and Co have kept the urge under control, avant-garde. After all, thousands of people may be gathering in the streets of Paris, but millions more are watching around the world. This closing ceremony at least felt like it was designed for the television audience.