New evidence shows that Greenland’s ice sheet once completely melted, exposing tundra beneath, suggesting increased vulnerability to climate change and significant potential sea level rise.

New research results provide direct evidence for the first time that in the recent geological past not only the edges but also the center of the Greenland ice sheet melted, creating a green tundra landscape on the island that is now covered in ice.

Surprising geological discoveries

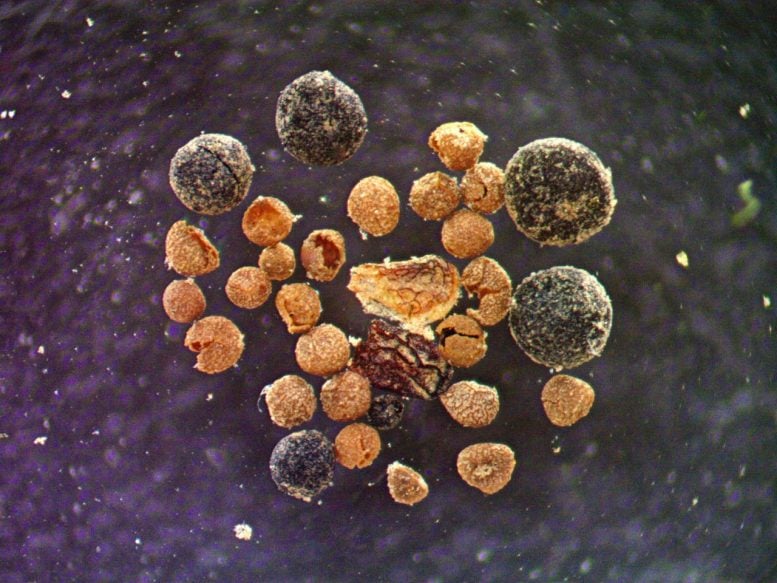

In the study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences On August 5, scientists re-examined a few centimeters of sediment from the bottom of a three-kilometer-deep ice core taken in central Greenland in 1993. To their astonishment, they discovered soil that contained willow wood, insect parts, fungi, and a poppy seed in pristine condition.

“These fossils are beautiful,” says Paul Bierman, a scientist at the University of Vermont who led the new study with UVM graduate student Halley Mastro and nine other researchers, “but yes, things are getting worse, which is what this says about the impact of human-caused climate change on the melting of the Greenland ice sheet.

Impact on global sea levels

These results confirm that Greenland’s ice melted and the island became green during a previous warm period that probably occurred within the last million years, suggesting that the vast ice sheet is more fragile than scientists thought.

If the ice in the center of the island melted, most of the rest of the ice must have melted too. “And that probably took many thousands of years,” Bierman said, enough time for soil to form and an ecosystem to take hold.

“This new study confirms and extends the idea that much of the sea level rise occurred at a time when the causes of warming were not particularly extreme,” said Richard Alley, a leading climate scientist at Pennsylvania State University who reviewed the new study. “It provides a warning of the damage we could cause if we continue to warm the climate.”

Sea levels are now rising by more than an inch every decade. “And they’re rising faster and faster,” Bierman said. By the end of this century, when today’s children are grandparents, they will likely be several feet higher. And unless the release of greenhouse gases — from burning fossil fuels — is radically reduced, he said, the almost complete melting of Greenland’s ice would cause sea levels to rise by about 25 feet over the next few centuries to a few millennia.

“Look at Boston, New York, Miami, Mumbai or any coastal city around the world and add more than 20 feet to the sea level,” Bierman said. “It goes underwater. Don’t buy a beach house.”

Reassessing the age of Greenland’s ice

In 2016, Jörg Schäfer was Columbia University and colleagues examined rocks from the bottom of the same 1993 ice core (called GISP2) and published a then-controversial study that suggested that the current Greenland ice sheet could not be more than 1.1 million years old; that there had been extended ice-free periods during the Pleistocene (the geologic period that began 2.7 million years ago); and that if the ice at the GISP2 site melted, 90% of the rest of Greenland would melt as well. This was an important step toward disproving the long-held belief that Greenland was an unforgiving fortress of ice, frozen solid for millions of years.

Then, in 2019, Paul Bierman of UVM and an international team examined another ice core taken in the 1960s at Camp Century near the coast of Greenland. They were stunned to discover twigs, seeds and insect parts at the bottom of that core – showing that the ice there had melted within the last 416,000 years. In other words, the walls of the ice fortress had collapsed much later than previously thought possible.

Evidence of former tundra ecosystems

“After we made the discovery at Camp Century, we thought, ‘Hey, what’s at the bottom of GISP2?'” said Bierman, a professor in UVM’s Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources and a fellow at the Gund Institute for Environment. Although the ice and rock in that core had been studied extensively, “nobody had examined the three-inch-thick moraine layer to see if it was soil and if it contained plant or insect remains,” he said. So he and his colleagues requested a sample from the bottom of the GISP2 core, which is kept at the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility in Lakewood, Colorado.

This new study in PNAS, conducted with support from the US National Science Foundation, now confirms that the 2016 “fragile Greenland” hypothesis is correct. And it underscores the concern, because it shows that the island was warm enough long enough for a complete tundra ecosystem, perhaps with stunted trees, to develop where the ice is now three kilometers thick.

“We now have direct evidence that not only has the ice disappeared, but that plants and insects lived there as well,” Bierman said. “And that is irrefutable. There is no need to rely on calculations or models.”

Uncovering the past

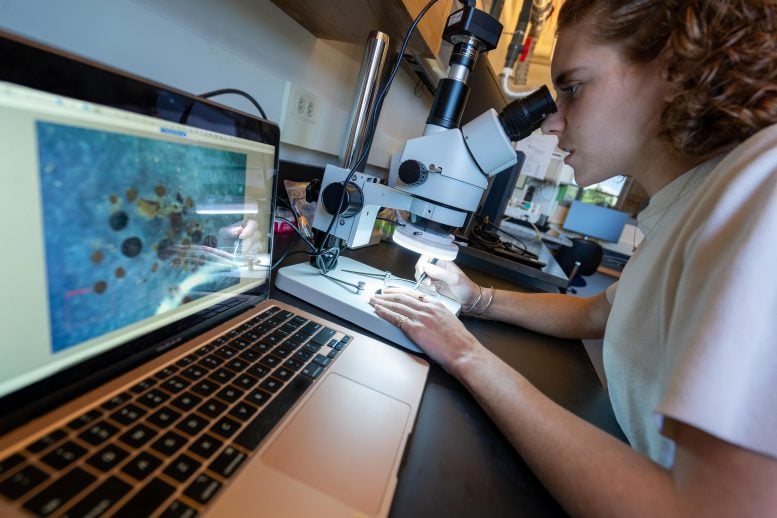

The first discovery that there was intact biological material at the bottom of the ice core—not just gravel and rock—was made by Andrew Christ, a UVM PhD geoscientist who was a postdoctoral fellow in Bierman’s lab. Then Halley Mastro took up the case and began studying the material in detail.

“It was incredible,” she said. What had looked under the microscope like small specks floating on the surface of the molten core sample was actually a window into a tundra landscape. Working with Dorothy Peteet, a macrofossil expert at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and co-author of the new study, Mastro was able to identify spores of salivary moss, the bud scale of a young willow and the compound eye of an insect. “And then we found Arctic poppy, just a single seed of it,” she said. “It’s a tiny flower that can adapt really well to the cold.”

But not so good. “It tells us that the Greenland ice melted and soil was created,” said Mastro, “because poppies don’t grow on miles of ice.”

Reference: “Plant, insect, and fungal fossils beneath the center of the Greenland ice sheet provide evidence for ice-free periods” by Paul R. Bierman, Halley M. Mastro, Dorothy M. Peteet, Lee B. Corbett, Eric J. Steig, Chris T. Halsted, Marc M. Caffee, Alan J. Hidy, Greg Balco, Ole Bennike, and Barry Rock, August 5, 2024, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2407465121